[ad_1]

During the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement’s first, seismic protests in 2018, a chant emerged and became an anthem for Pakistan’s thousands of disenchanted Pashtun youth.

Inqilab! Inqilab!

Zwanan mu qatal kegy

Da sanga azaadi da?

Pukthun pake gharqeqy

Da sanga azaadi da?

Da jwand berray mattegy

Da sanga azaadi da?

Inqilab! inqilab!

Revolution! Revolution!

Our young are being killed

What kind of freedom is this?

Pashtuns get ruined

What kind of freedom is this?

The ship of life is wrecked

What kind of freedom is this?

Revolution! Revolution!

Che na rakawe mung la huqooq da insaninyat

Pakar che bayad okrru spesalay baghawat

Azaadi! azaadi!

Malaly me guregy

Satruna ye mategy

Zwanan mu qatal kegy

Inqilab! Inqilab!

If they don’t give us our rights

We should rise in a daring rebellion

Freedom! Freedom!

Our Malalais are dishonoured

The sanctity of our homes is violated

Our young are being killed

Freedom! Freedom!

Da aman marghay jarrey pa dy bandy panjru

Bache zamunga khwar shu da stasu faislu ke

The birds of peace are crying in cages

Our kids’ lives have been ruined in your decisions

Zanzeer rana taawegy

Da sanga azaadi da

Awaaz mu na rasegy

Da sanga azaadi da

Inqilab! Inqilab!

We are being chained

What kind of freedom is this?

Our voice doesn’t reach out

What kind of freedom is this?

Revolution! Revolution!

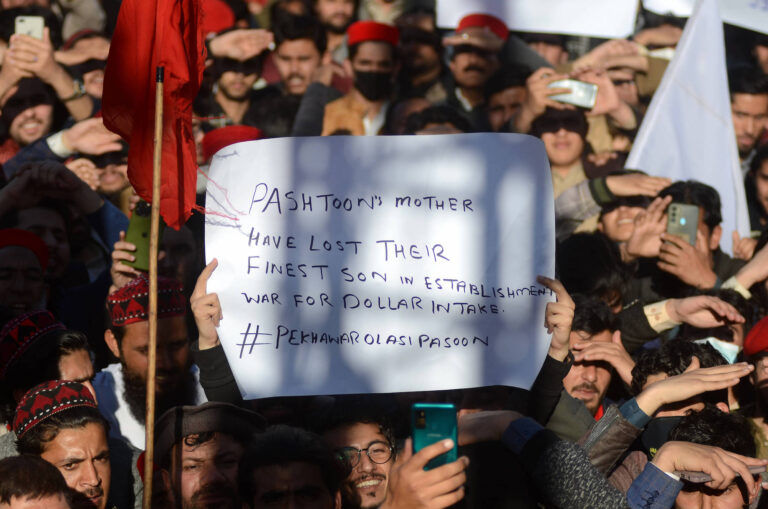

The PTM initially drew attention to the killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud, a Pashtun model and factory worker who was shot by Sindh police in Karachi. As the movement gathered force, their demands grew to include accountability for the killings, disappearances, torture and harassment routinely meted out to Pashtuns in Pakistan, and wider recognition of their rights under the country’s constitution. The PTM did not shy away from pinpointing as perpetrators of these violations both Pakistan’s military and security forces as well as Islamist militants active in Khyber Pakhtunkhwah, the Pashtun-majority province on the Afghanistan–Pakistan border. Over decades, the on-again, off-again relationship between these two groups had repeatedly devolved into brutal violence, with the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwah caught in the middle. Now, Pashtuns rose up peacefully against their treatment as pawns in this bloody game.

The PTM’s anthem drew on a long tradition of Pashto poetry – a potent and enduring form of expression and memory-keeping in the predominantly oral culture of the Pashtuns. The words articulated helplessness, frustration and collective loss, but nestled within was also a fierce desire for freedom. In this, the anthem illustrated an intense thematic shift in Pashtun poetry over the last 10 to 15 years, going from the subjects of love, mysticism and beauty that earlier dominated the tradition to ones of war, oppression and a longing for peace. The fact that these new themes have so rapidly displaced established older subjects is a measure of how intensely the violence of recent times – vastly exacerbated by the War on Terror and its ripple effects – has affected the Pashtun psyche. If Pashto poetry has always been the true cry of the Pashtun soul, today that cry is a blood-soaked lament.

The PTM anthem “Da sanga azadi da”, performed by Shaukat Aziz Wazir

Just as Pashtuns are marginalised in Pakistan, Pashto poetry is yet to get due recognition in Pakistan’s mainstream literary circles, despite its immense and vital tradition. Even a cursory glance at the programmes of popular events like the Lahore Literary Festival and the Karachi Literature Festival shows a fixation on certain themes to the exclusion of others. The clearest example of this is Partition, which is endlessly pored over – and which, tellingly, affected chiefly the provinces of Punjab and Sindh, which dominate power and politics in Pakistan to this day. In debates on social media, the argument has been made that the main victims of violence within Pakistan, including marginalised people such as the Pashtun and Baloch, have not produced anything that could be considered “literature”, and so cannot be included in these festivals. This offensive suggestion is echoed by the state. In effect, it amounts to an act of double violence: the perpetuation of state violence, and the erasure of minority voices by arguing that they are inaudible, irrelevant, or “not good enough”. In reality, there are floods of Pashto poetry – the beating heart of Pashtun literature – that deserve greater space and attention.

The PTM’s anthem drew on a long tradition of Pashto poetry – a potent and enduring form of expression and memory-keeping in the predominantly oral culture of the Pashtuns.

The first Pashto poem is widely considered to have been written by the warrior and poet Amir Kror Suri in the 8th century, although the historical authenticity of this is hotly contested, with experts considering the book cited as a source in support of this claim to be a forgery. The endurance of this belief despite the lack of hard textual evidence points to how stories and histories have always been handed down by word of mouth in Pashtun society, without the written traditions that are privileged by scholars today. Words – that is, spoken words – hold great importance for Pashtuns because of their unwritten code of conduct, called Pashtunwali. The phrase Jaba me kare – “Mein ne zuban di hai” in Urdu, or “I have given my word” in English, often used when making a promise, from business dealings to family matters – illustrates this point. Here, jaba” literally means tongue and figuratively means giving one’s word, which has to be honoured if you want to avoid the terrible charge of being bay-Pukhtu – “without Pashto”. The use of “Pashto” here has two meanings: it is a reference to the Pashtunwali code, and also stands in for “honour”. “Pashto”, then, simultaneously means the Pashtun language, honour and the laws of conduct. Pashto poetry contains all of this within it.

*

Now scattered across modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, primarily along the two countries’ shared border, Pashtuns have historically faced frequent challenges to their territories and ways of life. Most often, they have told stories about this in their poetry. By the 17th century, the eastern sections of Pashtun territory were ruled by the Mughals, while the western parts were ruled by the Persians. Naturally, Pashto poetry at the time focused on themes of resistance, against foreign invaders and central governments that tried to impose control over Pashtun lands.

Among the most prominent chroniclers of this period was the poet Abdur Rahman, better known as Rahman Baba. Raised among a small group of Mohmand settlers near Peshawar, by all accounts he lived a simple life, dedicated to learning. While there is no evidence that he joined the fight against the Mughals himself, in his verse he made clear where his allegiances lay:

Pa sabab da zalimano hakimano

Gore au aur au Peshawar dhray wara yo dee

Because of cruel rulers

Fire, the grave and Peshawar are all the same

Rahman Baba may have decided that the battlefield was not for him, but his contemporary Khushal Khattak chose differently. Born in 1613, in what is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwah, Khattak spent much of his time practicing sword-fighting and hunting. As a tribal chieftain, he experienced combat in his teens, even before he began writing poetry, earning him the title of “warrior poet”. His ancestors served the Mughals for years, and Khattak was also trusted by the Mughal court as a mansabdar, or administrative official, leading expeditions to suppress rebels in Punjab and the Afghan highlands. Despite this, Khattak was imprisoned in 1664 during the reign of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb – ostensibly over issues with tax collection, though the Pashto poet and writer Pareshan Khattak suggested the real reason was to curb his growing influence. Afterwards, Khushal Khattak’s poetry evidenced a transformation in his outlook, and he eventually took up arms against the Mughals, despite some of his family members choosing to remain loyal to them.

Just as Pashtuns are marginalised in Pakistan, Pashto poetry is yet to get due recognition in Pakistan’s mainstream literary circles, despite its immense and vital tradition.

Khushal Khattak and Rehman Baba are both icons of Pashtun resistance, but their work is very different. Rehman Baba’s verses were much more spiritual, focusing on God, mysticism and love. Khattak’s poetry revolved around honour, war, resistance and, most importantly, memory and freedom, as seen in this couplet:

Da Afghan pa nang me utarrala tura

Nangialy da zamane Khsuhal Khattak yam

I have taken up a sword in honour of Afghans

I am the one Khushal Khan Khattak of this age

Both Rehman Baba and Khushal Khattak expressed what it was like to have their culture and way of life threatened by invasion. Their poetry came to represent the collective voice of Pashtuns. Centuries later, mythology would come to play a critical role in maintaining this collective voice through the fable of Malalai, beloved for helping rally Pashtun troops against the British in the Battle of Maiwand in 1880, during the Second Anglo-Afghan War. (Malalai also features in the PTM’s anthem, immortalised in the line “Our Malalais are dishonoured”.)

The story goes that Malalai was living in the village of Khig, close to where the battle unfolded. Both her father and fiance joined the army of the Afghan emir, Mohammad Ayub Khan, to fight the British invaders. When the Afghan army seemed to be overwhelmed, despite having the advantage in numbers, Malalai, who was helping tend to the wounded, took off her veil and shouted:

Ka pa Maiwand ke shaheed na shwe

Khudayagu lalia be-nangay ta dy satey na

Young love! If you do not fall in the battle of Maiwand

By God, someone is saving you as a symbol of shame!

Seeing her courage, the Afghan army redoubled its efforts. When one of the flag-bearers fell, Malalai went forward and took up the flag herself (some versions say she fashioned a flag out of her veil), singing a landai, a kind of traditional Afghan poem:

Khaal ba da yaar la weenu kegdam

che sheenkey baagh ke gulab wa-sharma-weena

With a drop of my sweetheart’s blood

Shed in defence of the Motherland

Will I put a beauty spot on my forehead

Such as would put to shame the rose in the garden

It is said that Malalai was killed in battle but her words spurred the Afghans to victory.

*

While Pashto poetry has always contained stories of resistance, the corpus of Pashto poetry has mainly revolved around beauty and refinement. Mentions of janan (beloved) and masti (ecstasy) intermingled with husn (beauty) and wajood (existence). But Pashto poetry took on another dimension with the arbitrary delineation of borders that split the Pashtun heartland between contesting governments. In 1893, a formal agreement was signed between the British government in India and the emir of Afghanistan, Abdur Rahman Khan, creating the Durand Line. Its division of Pashtun lands sowed the seeds for violence and, eventually, militancy on both sides of this newly formed border.

Both Rehman Baba and Khushal Khattak expressed what it was like to have their culture and way of life threatened by invasion. Their poetry came to represent the collective voice of Pashtuns.

Ajmal Khattak, a celebrated Pashtun Marxist politician and poet, captured the frustration of Pashtuns in the aftermath. Born in 1925, as a student Khattak was an active member of the Quit India Movement, which called for an end to British rule in India. In adult life, he continued to speak up for Pashtun rights and become the president of the Awami National Party, a Pashtun-nationalist organisation formed in 1986. In 1973, after a crackdown against the ANP by the Pakistan government, Khattak was forced to flee to Afghanistan, where he spent 16 long years in exile. After his return, he was elected to Pakistan’s National Assembly in 1990.

Ajmal Khattak’s political struggle cannot be separated from his poetry, which represents perhaps the pinnacle of political and revolutionary poetry in Pashto, just as his poetry cannot be separated from his acts of political resistance.

Ghattan ghattan neekan neekan paida dy

Dwe khu la zaya janatyan paida dy

They have been born high and pure

Even by birth they are destined for heaven

Zay haghe khwaru la Jannat ogatay

Suk che da mura dozakhyan paida dy

Go! Earn heaven for those

Who by birth have been condemned to hell

These are excerpts from a long poem by Ajmal Khattak that was later popularised in song by Gulzar Alam, who rose to fame with his renditions of revolutionary songs in the 1980s, when Pashtun society was buffeted by the Afghan–Soviet War and rising religious extremism. In this poem, Khattak speaks eloquently of the censorship and repression that Pashtuns have long faced.

Pashto poetry took on another dimension with the arbitrary delineation of borders that split the Pashtun heartland between contesting governments.

Khattak’s poetry always referred back to the hopelessness of the downtrodden and their exploitation, dealing with questions of class, political freedom and violence on Pashtun land. His verse also touched on themes of rebellion, frustration and love in equal measure. Similar messages can be found in the work of Rahmat Shah Sail, born in 1950 into such poverty that he was forced to drop out of school. Sail worked as a tailor near his hometown in what is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwah. He began composing poetry early in life, turning to it as a salve after long days of work.

Za da mohabbat da gulu tukham yam

Khawre ba me khaware na zarghun ba sham

Wakhta ta dy waas okrra che orak me key

Za ba azan paida krram, Pukhtun ba sham

I am seed of flower of love

Soil won’t absorb me but I will flower

Oh Time! Try all to erase me

I will bring myself into existence: I will become Pashtun

Sail’s words capture Pashtuns’s ability to find and create great beauty amid great hardship, and they defined this era of Pashtun poetry. But such verse would fade away with the arrival of 9/11 and the War on Terror.

*

On the Pakistan side of the border, the violence of the Taliban and various other militant groups – often in response to ordinary people trying to stand up to militants and push them out of their home areas – rendered Pashtun civilians silent and numb. How else could people react to the bombing of Meena bazaar in Peshawar in October 2009, which resulted in more than 130 deaths? What words could adequately describe the pain of losing 105 people who were watching a volleyball match in Lakki Marwat, in 2010? What consolation could there be for a neighbourhood that gathered to offer funeral prayers for a slain police officer in Swat in 2008 only for a suicide bomber to send 38 from the same neighbourhood to their deaths? As Pashtuns, we witnessed a funeral procession from what seemed like every other home – not once, not twice, but countless times, enough that the mere numbers came to be almost meaningless.

Eventually, ordinary Pashtuns began to speak again, and they expressed themselves in poetry. The very tone and timbre had shifted, and the common words and themes now were jang (war), aman (peace), zulm (oppression). Janan (beloved) has been replaced by jang, while the yearning for masti (ecstasy) has been taken over by a longing for peace. Earlier, wajood (existence) was the overarching concern, but now wajood and zulm coalesced around a new consciousness of a body politic under threat of annihilation.

These changes define the Pashto poetry of the present day. As the young poet Ali Khan Umeed says:

Dalta da bal shante da sarru raaj dy

Dalta da ghatu topaku raaj dy

Pa hagha kaly ke dolay qaht shwe

Bas pa ogu da janazu raaj dy

This land is ruled by another type of creature

This land is ruled by big guns

Listen! There is a famine of dolis in that town

Shoulders are used for carrying funeral biers instead

Here, Umeed uses powerful cultural symbols to convey the new realities of life. In Pashtun lands – including Swat, the poet’s home – it was tradition to carry a bride from her parents’ house to her new home on a doli, a special palanquin decorated with flowers, mirrors and crystals. Now, Pashtun men use their shoulders to carry funeral biers to graveyards instead.

During the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement’s first, seismic protests in 2018, a chant emerged and became an anthem for Pakistan’s thousands of disenchanted Pashtun youth.

This transition from past to horrid present is the core subject matter of Umeed’s poetry. He grew up in the Swat Valley, and in his late twenties he lost his best friend in a massacre. This was in 2014, when gunmen affiliated with the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan stormed the Army Public School in Peshawar, killing at least 144 people – 132 of them schoolchildren. Umeed describes the trauma of this loss and the economic conditions of Swat amid the ravages of war:

Pa speena jaama patt day, da sarray zma qaatil dy

Pa ma che raghwrrege, da sarray zma qaatil dy

Pa marg lapasa mrama pa elaj ye na pohegam

Be-yaara che ra dromee makhamay zma qaatil dy

Clad in white, he is my killer

The one shrieking out loud is my killer

I am being killed after I died

An evening spent without my beloved is my killer

Hujra jumaat maktab ye pa srru weenu ke khroob krral

Khkaregy na khu da dagha khunarrey zma qaatil dy

Zma da janaze awalne saff ke walarr dy

Za sanga pa khula owaim che flaney zma qaatil dy

Hujra (community space), mosque and school have been dyed red by blood

Invisible is he, but he is my killer

He is standing in the first row of my funeral prayers

How can I say that he is my killer

Umeed is a romantic through and through, but it is as if his conscience will not allow him to evade the grim reality he is living in. Romantic words “flower”, “beloved” and “forlorn” intermingle with words like “graveyard”, “blood” and “massacre”. And, always, there is a deep immersion in the Pashtun cultural world – as here with the reference to the hujra, which are important community spaces for Pashtun males from the same family or neighbourhood, often functioning as guest house, wedding space, entertainment venue and local council.

Ali Khan Umeed performing “Bas kafiro ta me bozai”

Umeed has published three books of poetry so far. He is always burdened by the discrepancy between his creative freedom and his constrained material existence. In one of his most popular poems, which has been widely shared on social media and performed by a young singer from Swat, he says:

Pa qadam pa qadam nakaam dy

Bas kafiro ta me bozai

Dalta adam istehkaam dy

Bas kafiro ta me bozai …

At every step there’s a failure

Take me to a faraway land not ruled by Muslims

There’s instability

Take me to a faraway land not ruled by Muslims …

Da dy khar laaru kusu ke

Kakaray da jwand praty dy

Dalta shawe qatal-e-aam dy

Bas kafiro ta me bozai

In the streets of this city

Heads cut off from bodies lie

This is the sight of a massacre

Take me to a faraway land not ruled by Muslims

Kafiro or Kafaru can translate literally to “non-believers”, though it is often interpreted to mean non-Muslims, though this is subject to some debate). Here, the phrase is used with a bit of irony. Rather than seeing a land ruled by kafiro as something to be shunned – something not uncommon in Islamic cultures – Umeed expresses a kind of attraction to it. Here, the kafiro-ruled land can be taken to mean a faraway place where injustice is not perpetrated by those belonging to the same religious community as oneself. The poem highlights the oppression faced by Pashtuns across multiple fault-lines. There is a strong push against the state narrative of Islam as the prime binding force in Pakistan, with all non-religious identities seen as distractions to be erased. Umeed also expresses the lament of the ordinary citizen, a sense of frustration with and a desire to escape from one’s own land.

A similar sense of yearning for escape can be found in the work of Nisar Wazir, a poet from Waziristan:

Gard Pukhtana dar ba dar dy ta ba kala razey

Da aman sulhe peyambara ta ba kala razey …

All the Pashtuns are displaced, when will you come?

O the Messenger of Peace and Truce, when will you come? …

Da rrang watan da kaduwalu sakha sar obasama

Da aday mur zargiya, zegara ta ba kala razey

I peep out of the demolished buildings of the demolished land,

O Ye heart and bosom of the mother, when will you come? …

Che bya pa yaua tapa da lar au bar lakhkar yau krre

Ay, da Malalay inzur gara ta ba kala razey

When will emerge a person like Malalai (of Maiwand)

That may unite the Pashtuns of East and west by a single Tappa?

(The translation in English is taken from Standing above the rubble.)

This verse, and this translation, is part of Standing above the rubble: An anthology of peace poetry from Waziristan, compiled by the anthropologist Ashraf Kakar and published in 2021. The poem reflects the helplessness of the present but also yearns for a new tomorrow. The mention of Malalai of Maiwand also points to a new awareness of women being part of the struggle – something rarely seen in traditional resistance poetry in Pashto.

Pashtuns have historically faced frequent challenges to their territories and ways of life. Most often, they have told stories about this in their poetry.

Both this poem and Umeed’s “Bas kafiro ta me bozai” are anti-war and anti-violence. What they also have in common is a clash between traditional tropes of love, loneliness and separation from the beloved, and newer themes dealing with conflict, collective loss and trauma.

This clash can also be seen in many recent Pashto poems that have become popular on social media. Some of them have been set to music by various popular singers, and their poets have been able to gain massive social-media followings as a result. One such poet is Muneer Buneray, from Buner, adjacent to Swat.

Weene ta oba way ka jwand kawe

Speene speene ma way aka jwand kawe

Kufar ta da sara kufar ma waya

Marrey ta oda way ka jwand kawe

Spy ta azmaray kargha ta baaz waya

Spaku ta drana way aka jwand kawe

Dalta jwand pa luy munafiqat kegy

Zahru ta khwaga way aka jwand kawe

Ya Muneera zan be-neetay ma wajna

Baddu ta me kha way ka jwand kawe

Call the blood water, if you want to live

Don’t tell the plain truth, if you want to live

Never call out cruelty

Call a corpse a living being

Call a dog a tiger, and a crow an eagle

Label the vulgar as respected, if you want to live

Being alive takes a lot of hypocrisy here

Call poison sweet, if you want to live

Oh! Muneer, don’t kill yourself before your time

Call the evil good, if you want to live

Buneray’s poem points to two realities: life under the Taliban and the impact of military operations against the Taliban. To fight the militants, the Pakistan military imposed strict bans in the territories under their control against any questioning of its operations. Here, in simple language, Buneray shows the toll of self-censorship in a repressive regime.

The range of voices in Pashto poetry today is much wider than can be shown in just this essay, for which I had to content myself with just one voice from Swat in Ali Khan Umeed, and one anthology of peace poems from Waziristan. The poets I have cited are also all men, since it is their voices that come through in the Pashtun public sphere. Pashtun women poets exist, but their lack of mainstream exposure reveals the patriarchal violence still alive in Pashtun society. As an example of the risks women poets face to write and perform poetry, consider the case of the Afghan lyricist Rahila Moska, who took her own life after her family caught her reading over the phone for a poetry gathering. No matter how eloquently Pashto poetry articulates the trauma of war and violence against the Pashtun people, as long as the tradition fails to include women’s voices it will carry within itself a latent violence. Ending this terrible exclusion must be the next change in the life of Pashto poetry.

Note: All English translations are the writer’s own except where otherwise stated.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece misattributed several lines of verse to Khushal Khattak and Ajmal Khattak. These have been removed or replaced. Himal Southasian regrets the errors.

***

[ad_2]

Source link